It was also some time before artists began to adopt the crucifixion as a theme. In fact no depictions of Christ survive from the first two centuries after his death. Early Christians upheld the second prohibition of the Ten Commandments and strictly forbade any form of idolatry (Exodus 20:4). In the third century, successive Roman emperors continued to persecute the growing Christian community: one response of Christians was to develop secret symbols that only the initiated knew and recognised. A major change occurred in the early fourth century: in 313, Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. Later, in 381, Emperor Theodosius made it the state religion. It was after this that the first depictions of the crucifixion began to appear.

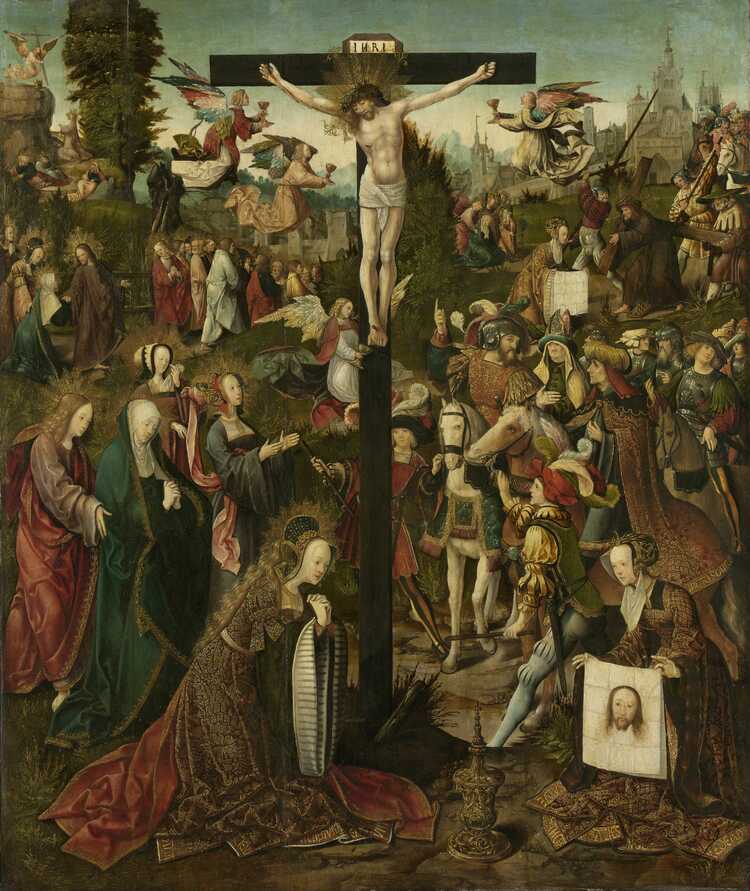

Over the centuries, Christ came to be perceived as crowned in divine majesty: victorious over death and triumphant over human suffering. He was depicted surrounded by his loved ones, with symbols expressing Christian themes. These depictions of a stoic, superhuman Christ made way in the early twelfth century for a more accessible Christ, a man who suffered the extreme physical trial which his Father had imposed. He appears on the cross as an emaciated, pitiful man. The spikes of his crown of thorns pierce his skull. His body has the pallor of death and his posture is contorted. For a late mediaeval Christian there would have been little doubt: the sacrifice that Christ made to free man of sin was immeasurably great.

Artists did not depict Christ dying alone. Crowds would be shown thronging around the cross: a growing number of intimate friends and followers. For the devout onlooker it was possible to imagine actually being there and to empathise with the gathering mourners.

In the Gospel, Christ enjoins John, the disciple whom he loved, to look after his mother after he dies (St John 19:26-27). Both are already depicted in the earliest crucifixion scenes of the Carolingian period. The Virgin Mary is to Christ’s right, nearest his heart; St John is on his left. Both are standing. Their pose is subdued; their heads bowed. Sometimes, Mary is shown holding her chin in a gesture of confusion, supporting her elbow with her other hand.

In later centuries, artists express the emotions of the onlookers more freely. St John appears on the right, catching Mary as she faints: she had revealed to the mystic St Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373) in a vision that she collapsed in a daze when she saw her son crucified. In her writings, Bridget describes Mary in the comforting arms of St John.

Van Oostsanen was familiar with this late mediaeval iconography and with his evident disdain for empty space he crammed his depiction of the crucifixion full of people. That Jacob was above all concerned with aesthetic beauty is clear from his depiction of Christ: no gruesome gore there.