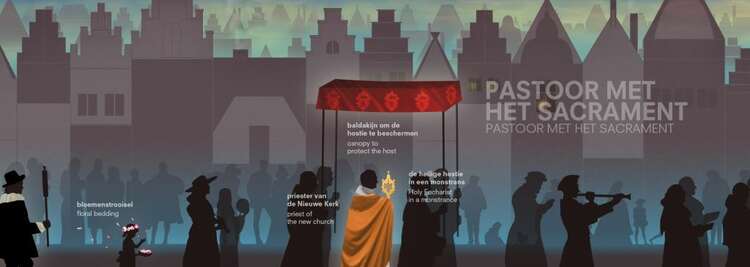

Leading the way in the mediaeval procession were representatives of the craft guilds; the youngest guild first. They would carry guild symbols, brightly coloured statues of patron saints and burning torches. Following them came young girls symbolising the Virgin Mary and other saints, after which St George on a horse, dragging a dragon on wheels. After all this holiness, the parade featured angels and demons chasing each other in the street: the angels dressed in white, with gold wings on their shoulders. They played drums and cymbals. The devils would wear gruesome costumes and a mask with a terrifying smile, and would wield sticks. They walked around about to create space for the procession to continue, scaring the children, who would start to cry as the blackened demons ran up to them. After them came the three militia guilds: guardsmen with arms and armour. One of these would be the winner of annual parrot-shooting competition, carrying his silver parrot trophy. Wine would be poured and the civic guard squads would toast the parrot king, and eat and drink their fill as the procession continued. After them came choristers, singing loudly, and then priests carrying silver statues. White damask banners would flutter behind them. The leader of the Franciscans would carry a crucifix high on a standard. The Sacrament was not far off, blocked from sight by men and women in white, atoning for their sins and leading the holy relic. The four burgomasters held up a canopy of gold cloth, covering a priest holding the monstrance. The Sacrament would be accompanied by town musicians playing sweet, melodious tunes on pipes, shawms and other musical instruments. Bringing up the rear were other town functionaries and the common folk. Doubtless these would also include the many pilgrims who came from far and wide.

This was how Walich Syvaertsz (1546-1606) recalled the procession. This Amsterdam apothecary, a devout Calvinist, recorded his memories of the procession in 1604, in his Roomsche Mysteriën (Roman Mysteries). His writings are a diatribe against papist heretics; but his description reads like pure nostalgia. Thanks to his childhood memories we know what the procession must have looked like in the years preceding the Protestant takeover of the city in 1578. A greater contrast with today’s solemn procession could hardly be imagined.

The procession in the age of Jacob

Last Saturday, 22 March, was the night of the Silent Procession. Each year, around 10,000 worshippers come from all around to walk the hallowed route. In the dead of night, silently mouthing prayers, with no fanfare or symbols. The silent footsteps reverberate through the bawdy centre of town. It must have been different five centuries ago, in the age of Jacob van Oostsanen.

117 keer bekeken