The superdiversity of their cities is not reflected in the staff of city museums in the large cities of Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. At the Antwerp symposium on city museums and migration, very few of the directors, curators, and educators had a migrant background.

Superdiversity, a term coined by Stephan Vertovec in 2006, has since become a buzzword among city museums. How can we represent the superdiverse cities of today? And, equally important, how can city museums be meaningful for the superdiverse population? With some 60 millions migrants throughout Europe, migration has resulted in cities where people of migrant backgrounds are becoming the majority. How can we tell that story, or rather stories? Unlike in the 1980s and 1990s, when many museums created separate exhibitions about various ethnic groups, today’s trend is to make the whole museum narrative more inclusive.

One way out of the dilemma of superdiversity is the biographical approach. Our host during the first day, the recently opened Red Star Line Museum, is a good example. Although the overall perspective of the museum is that of the 3rd class (2nd and 1st class experiences are in the museum’s scenography higher up, as if seen from below), the stories show a great variety in country of origin, gender, age, position in the chain of migration, and of course luck. The museum hopes that the personal stories of people seeking a better live will lead to identification. A Belgian minister who wanted to expel a young refugee was told by the media to go and visit the Red Star Line Museum.

Boutique multiculturalism

Prof. Ching Lin Pang (University of Antwerp, University of Leuven) was six when she arrived in Antwerp 45 years ago. She calls herself a stubborn believer that migration and multiculturalism will lead to a better life and better world. She presented us with some examples from sociology and anthropology. Sharon Zukin, for instance, analysed how the New York urban landscape has changed from production to consumption, not only of food but also of culture. And of course Prof. Ching Lin Pang spoke about the concept of “museums as contact zones” developed by James Clifford. In cities there is conflict and ideas are constantly contested, so museums need to be spaces where these issues are discussed. Ideally visitors are involved in both the construction and the deconstruction of the museum.

New museology, born out of the happy marriage between anthropology and museology, created the idea (and sometimes the practice) of the museum as an interpretation center with the power to name the unnamed. It is not always easy to create a contact zone that encourages a contestation of views. Many museums react to media reports on the conflicts surrounding migration by stressing the positive. Therefore they are sometimes accused of celebrating multidiversity. “Boutique multiculturalism,” coined by Stanley Fish was the new buzzword of the Antwerp conference. Lin Pang: “In the UK, lamb curry is accepted but niqab or burqa is not. Chicken tikka massala is truly British and a good example of boutique multiculturism. Massala sauce was created because the British wanted something resembling gravy. With food, absorbing new tastes is easy, with religions it’s already somewhat more complicated.”

For most people working in museums, the objects in the museum’s displays and storage rooms are very real. It is always useful, as Lin Pang did, to remind ourselves that philosophers like Jean Baudrillard think of objects in the modern world as simulacra, more symbol than physical fact. Museums, like all cultural institutions, interpret; we depend on narratives, socially shared narratives. Ching Lin Pang told us about a student of hers who went behind the scenes of the Museum of London and the Dockland museum to study their narratives of migration. She interviewed visitors in the MoL, mostly elderly white women. The student concluded that the museum does not provide the full picture. There is a disconnect between museum experience and real life. The narrative lacked stories about tension related to migration, especially in early periods. In the Docklands Museum, however, the visit did have a transformative effect on visitors, mostly due to a realistic walk through the slavery experience. It unleashed a lot of emotions, unease, and guilt, and visitors even apologized to the student, a black woman from the United States. Lin Pang did wonder what Baudrilliard would have to say about the hyperreal slavery video. She ended by concluding that normally museums do not get push the visitor out of his or her comfort zone. Few museum staff stop to pause every now and then to think about the framer and the framed, about how some see museums as exploitative, distorting realities like a game of telephone in which the message never emerges the same way it entered. We need to listen to accusations that museums steal and transform “our stories,” no matter how much we do our best to work from “bottom-up perspectives.”

Mainstreaming migration

The renovated city museum of Hamburg, explained Marta Bobowski, fellow of migration and cultural diversity, will treat migration as a network process and show its influences on the city. Biographies and interviews will give the personal angle, and multimedia installations will focus on the topography of migration. It will not concentrate on differences, as an ethnographic museum would, nor show only positive stereotypes. Marta is one of the fellows with a migration background that are part of a training program in German museums.

Groups of migrants

Museum Rotterdam has been out in the city a lot during the last years. In preparation for the move to a new building, it developed a visitor matrix (together with bureau Muzus) in order to find out who their visitors are. Jacques Borger, advisor for strategy, marketing and partnerships: “We realized migrants mostly come as groups, with schools or migrant organizations.” The “colourful strivers” is one of the groups the Museum Rotterdam wants to attract. Borger and his team researched their wishes for the museum, as they did with the other groups: urban omnivores, active families, and suburban pleasure seekers. They found that the strivers feel very connected to Rotterdam, are part of extended families, and have a great network. Most of them see little use in going to a museum; they would rather go on a family picnic or buy clothes.

For the colourful strivers, sharing (museum) experiences in a group is important. They prefer oral information to flyers and like to be welcomed with advice on the route through the museum. Museum Rotterdam is even thinking about changing its name to something other than “museum.” For many, “museum” means art for rich and white people. A museum should be an urban shelter, a place for inspiration that helps citizens tell the story of us.

Geschichte wird gemacht

The Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Museum, where San Francisco-born Sophie Perl is a curator-in-training, was founded in 1991. It has 450 m2 of exhibition space and 3 permanent employees. The neighbourhood of the museum is undergoing extreme gentrification. Ever since its founding, the museum has worked from the bottom up rather than top down. Anybody interested in writing and showing (their) history was welcome. Sophie talked about the exhibition “Geschichte wird gemacht” (opened in 2003). After an open call for participation, 60 people took part. The museum coordinated the meetings of the group, which resulted in an atypical historical canon full of protest movements and squatters. The participants mainly came from the leftist movement; very few migrants responded to the open call. The exhibition “Ortsgesprache” about migration about urban diversity was more curator-led and less organic than “Geschichte wird gemacht.” Maps with numbers provide access to short audio stories on an iPod. One of the year’s highlights was an Iftar (fastbreaking dinner) with 600 people during Ramadan. Afterwards the staff wondered if this should be the core mission of the museum, however utopian the event felt for the participants.

Spoorzoekers/Traceseekers

Lieve Willekens, curator at MAS, explained how the Spoorzoekers (Traceseekers) aimed at uncovering stories and objects related to the Moroccan community of Antwerp. 32 people joined the project, from Rose, a elderly woman who had worked with Moroccan guest workers, to Hasna, a young woman whose father, one of the guest workers, died when she was 2. The results are shown in a small exhibition about 50 years of migrant labour, which also includes Turkish examples. Events were organized around the exhibition such as a “calligraffiti workshop.” Some of the Spoorzoekers continued their research within the context of other exhibitions such as “Holy Places” or an exhibition about local shops. Not all events were equally successful.

In a recent project, the Red Star Line museum used Instagram to collect. People contributed over 1000 photos from holidays to their countries of origin over Instagram #rslreis, which could be read as selfies about identity. There are different storage places for stories, for instance Het magazijn, where digital stories are kept. For the RSL, classes are ideal groups to talk to about migration.

Paul van de Laar concluded at the end of day 1: “We are the believers in exhibiting our superdiverse urban societies, but what do academics have to say about our work? We have to convince them, but also our board and local politicians, who want us to tell single narratives. There are no single narratives.” Museum Rotterdam, like most other city museums, is too big to turn into a bottom-up organization. “We may have our methodology right, but the proof of the pudding is: are people coming to our museums? Maybe we have to invite superdiverse people and ask them to interpret our stories.”

Exhibiting cultures

Leen Beyer welcomes us for the second day at the MAS and tells us a little bit about changes in the team of the new museum: The person responsible for outreach became part of the curatorial team. Now the marketing department has to become aware of the multicultural media landscape of the city.

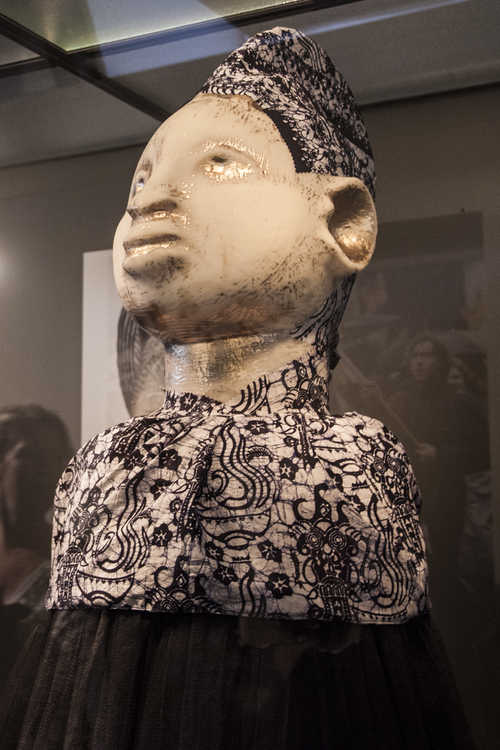

Symposium 'Urban Diversity and Migration - Photo taken in the Red Star Line Museum

Joachim Baur, our keynote speaker on the second day, has reseached migrant museums in the United States and Canada. He referred to Karp and Lavine’s “Exhibiting cultures,” as well as to James Clifford, who called culture “a deeply compromised idea I cannot do without.”

All of the migrant museums have an inclusive master narrative about migration as a shared and uniting experience. They all underline diversity, although not always as migrant communities themselves would like. Greek visitors objected to a photo in Ellis Island of drinking Greeks with guns, as they felt it misrepresented them. Most migration museums leave out slavery. In Ellis Island it proved difficult to include transatlantic slavery, since people were reluctant to give objects. There are few “unsafe” stories in migration museums. Baur discovered by chance that a man named Meil Black was presented in Melbourne’s Immigration Museum as a “good immigrant,” but in the Melbourne Museum he discovered that Meil Black had been involved in killing Aboriginals.

Migration museums are remarkably similar with some tropes that appear everywhere. Visual metaphors like borders (and passports) emphasize the strong role of the state in distinguishing between desirable and undesirable migrants, detracting from the agency of migrants. Another metaphor is the journey, often with parts of ships, always with suitcases as iconic objects that also play with the relation between the visible and the invisible. The “cornucopia” (colourful mix of objects) in the migration museums’ glass cases is in itself a metaphor for immigrant societies.

The Tenement Museum in New York focuses more on migrants’ agency and their life-and-work biographies. It concentrates on place and placemaking, just like the Migropolis project in Venice. In the “Route der Migration” – a scattering of containers all over Berlin showing the different layers of migration – the placemaking aspects of migration played a major role. Baur is curious to see the outcome of the Museum Friedland, located in a still-operational refugee center in Gottingen. Some fear that it could become a refugee zoo. But the museum could also serve as a contact zone with refugees being trained as tour guides.

In the next session, curators from the STAM in Ghent spoke about “Sticking Around: Fifty years of migration to Ghent,” a project presented outside of the museum with exhibits in the streets and in places that have a relation to migration history, as well as with successful walking tours.

Director Jan Gerchow and Puneh Henning, fellow of migration and cultural diversity at the Historisches Museum Frankfurt, told us about the ongoing Stadtlabor project in Frankfurt. It created a dialogue between citizens in various neighborhoods, and the results will be included in the new Frankfurt history museum.

Kitty Jansen (Museum het Domein, Sittard) observed that most of the people making exhibitions about migration do not come from migrant groups. In Sittard they started by asking the population what people wanted to know, for example, about their Moroccan fellow citizens. “Do they hit their wives?” some schoolchildren wanted to know. She hesitates, however, to make exhibitions that label people as a group. Grouping people together can reinforce stereotypes, such a calling the murder of one’s wife a “crime of passion” when the culprit is of Durch origin and an “honor killing” (eerwraak) when it happens in the Moroccan community.

After the presentations, Bambi Cueppens of the Afrikamuseum in Tervuren wondered why the Amsterdam Museum’s presentation was the only one that dealt with migration related to the colonial past. I spoke about the Kabra (ancestor) mask that was recently acquired by the Amsterdam Museum. It was created through a 3-D scan of an original African mask and serves not only as a museum object but also as an object in rituals outside the museum.

During the final discussion, participants wondered why some of our exhibitions are so positive. So much negative news around migrants appears in the media, and we want to show something positive. We may also feel uncomfortable with negativity. Remarkably, only in the discussion did the STAM curators tell us that the exhibits in the streets were destroyed several times.

Photo taken by Caro Bonink - Amsterdam Museum

Do we need objects? This was another question. The story behind the objects is often invisible, and many objects are not very attractive to other visitors. The Cologne Museum’s audiotour turns the dynamic around: migrants comment on museum objects.

Anja Dauschek, director of the Stadtmuseum Stuttgart, concluded the conference. Her remarks again focused on the question: How do we approach the communities, and how do we avoid the trap of boutique multiculturalism? How to deal with difficult stories and conflicts could be the subject of a next meeting. Rather than objects, we should maybe concentrate more on places, a good starting point to show the complexities and layers of migration. Maps inside and outside the museum can integrate the city into the museum area and make the present and the future a stronger part of our presentations.

Annemarie de Wildt

Curator, Amsterdam Museum

(many thanks to Sophie Perl for editing the text)