Mutuality was the key word in this training - as part of the Shared Cultural Heritage Program, both the Ministries of Education , Culture and Science and Foreign Affairs were involved. The National Cultural Heritage Agency organized the training together with Reinwardt Academy. The Amsterdam Museum served as the laboratory for case studies about addressing disputed and contested stories in museum practice. The trainees, comprised of fifteen women and three men, all came from countries that have a shared history with the Netherlands: Suriname, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, Sri Lanka, United States, Russia, India, and Thailand. The trainees were inspired by lectures on, among other topics, narratives spaces and empathy in the museum. They participated in an emotion networking workshop, boarded a boat with the Black Heritage Amsterdam Tour, and had 'behind the scenes' discussions at the Rijksmuseum, Mauritshuis, and Tropenmuseum, among others.

The concept behind this training was sparked by curiosity about the influence of the international and colonial history of the Netherlands, "the language we speak, the food we eat, the buildings that surround us, and the stories convey many traces of a history that we share with other countries." Shared cultural heritage can be both a pleasure and a burden. It is a pleasure because a shared past joins us together, fostering wonder and commonalities. But it is also cumbersome and complicated because much of that shared heritage is rooted in painful histories. This is the 'multi-layered texture of coloniality', as it is called in heritage jargon.

Dilemmas about disputed places

The Amsterdam Museum thus functioned as a laboratory and workshop. We invited participants to apply their 'deconstruction strategy' on four spaces in the permanent exhibitions Amsterdam DNA and World-City. We shared our dilemmas with them concerning disputed places in these exhibitions, such as the wall about slavery in the 'Golden Age' room and the tone-of-voice of the audio tour. We asked them to look at how contested histories are told and shown, and to look into the function and organization of texts and objects. The trainees, broken into four teams, each chose a space. During the two week program, the trainees spent many hours in 'the Golden Room', 'the Map Room', 'the Pink Room' and 'World-City Revisited'. They analyzed the narrative space, objects, texts, and wall color. Then they shared their findings with the curators and educators of the museum. The last day of the training, a quiet Friday morning, we walked with the trainees, trainers, coaches, and a number of colleagues from the Amsterdam Museum, through our permanent exhibitions. What had they remarked about the way we tell the story of Amsterdam to our visitors from Amsterdam and the world?

Discomforts in the Golden Room

Team Golden Room kicks off. Their vision covers the whole world: Ajeng Ayu Arainikasih from Indonesia, now a Ph.D student in Leiden; Dakaya Lenz, whom I already knew as the content director of the great (children's) museum Villa Zapakara in Paramaribo; Dirceu Marroquim, who worked in Recife in museums and with intangible cultural heritage and now also is a Ph.D student; Lankani Somarathna, assistant director at National Museums in Sri Lanka; all of them come from countries where the VOC or WIC once held the reins. It is quite painful to hear Ajeng, with her Indonesian accent, imitate the voice in the audio tour, which sounds like a cheerful commercial: "Amsterdam merchants dominate WORLD TRADE. Everything Amsterdam touches turned into GOLD. The city co-owned Suriname where Africans were forced to work as SLAVES. (These words in capital letters indeed sound like that). As far as they are concerned, the audio tour is among the biggest discomforts in this room due to the exclusion of people from Surinam, the Antilles, South Africa and Indonesia, whose ancestors were these slaves. How can you add their perspective?

The 'Golden Room' in Amsterdam DNA in front of the infographics wall on slavery, photo Annemarie de Wildt

In my introduction at the beginning of the training I told them the museum in June 2018 removed one of the drawings on the red infographics wall because of criticism from Simone Zeefuik and other people connected to #Decolonizethemuseum on the 'dehumanizing' way in which the Amsterdam Museum portrays enslaved people here. Dirceu brings his Brazilian knowledge and notes that in a remaining drawing of slaves who cut sugar cane, the reed is drawn much too large. He adds with a smile: 'that was how it was, the yields of the sugarcane were more important than the people who worked it'.

And the diorama inspired by the Waterland plantation painting, what does that mean? Why so little explanation? Very useful questions, some of which we have asked ourselves. In any case, asking questions might be better than telling a story, especially if that is too much of a 'single story'. The Golden Age hall is full of portraits of white people, individuals with a face. Black people are icons without faces. Where are their faces and their emotions? Their perspective and voices should be added, advocates the Team Golden Room.

Map Room

The Map Room team investigated the first room in Amsterdam World-City, a part of the permanent exhibition that opened in 2018. It consist of Amanda Massie, who works at the New York State's Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation; Gunjan Joshi, program coordinator of Intangible Cultural Heritage at the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage; Juliana da Mata Cunha, who deals with Brazilian and Dutch heritage in the state of Pernambuco, in Brazil; Kaori Akiyama, researcher at the National Museum of Japanese History; and Sergei Balandin, curator at the Victoria Art Gallery in Russia.

Team Map Room with the mapmaker in the background, photo Annemarie de Wildt

In this room too, the team thinks that people and faces are missing. The only real portrait in this room is a white man, the mapmaker Joan Blaeu. Although the maps on the floor depict indigenous people, their function in the room is just like on the maps themselves: decoration. The richness of their culture remains invisible. In the 17th and 18th centuries Dutch maps paved the way to the riches in the rest of the world, but they do not reflect what the conquest and trade meant for the people who lived there. Maps are also about power and the museum could make that more explicit.

Their commentary also concerns an issue the World-City team, that created the exhibition, has talked about: where should the enslaved be placed in the moving maps projected on the wall; within the migration maps or within the map about the movements of commodities and the merchandise? They choose for migration. Perhaps the museum should make this kind of dilemma more visible. The addition of more objects, the products of this often unequal trade, information about the way these products came to Amsterdam and who was involved, could make the room richer and above all more human. The audio tour could literally provide greater multivocality.

Kaori Akiyama discusses the migration and trade video's. Photo Annemarie de Wildt

The team notes, which we also did at the New Narrative meeting about the painting of Plantation Waterland, it is a pity that there is no connection made between the painting and the map of Suriname on the floor or with the names of the slaves, who worked there under duress. ‘Words matter’ - the title of a book with which the trainees became acquainted at the Tropenmuseum. In the title of the room the word settlement is used, for the majority this word has associations with colonization by a foreign ruler.

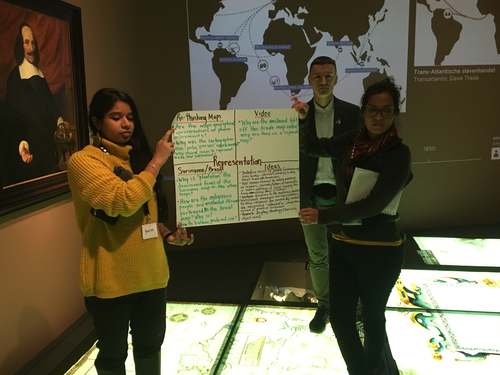

Team Map Room with their analysis of the space, photo Annemarie de Wildt

The Pink Room - the image of Amsterdam

The team of the Pink Room was also very international: Aomi Mochida from Japan is currently residing in the Netherlands working on her thesis about WOII; Femke Veeman, the only Dutch participant, coordinates the education at EYE Film Museum; Liya Chechik is responsible for the Public Programs at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center in Moscow; Rizky Fardhyan is working on a World Heritage Nomination in Sawahlunto, Indonesia; and Inez McGregor is working at an archive of the anti-apartheid movement in Johannesburg. They spent a lot of hours between the dyed pink walls of the room and also observed visitors. The conclusion: it is not clear what this room is about. There are three perspectives: marketing (how does Amsterdam sell itself), identity (how does the city see itself), and how do others see the city. These quotes are by very negative people from Rotterdam, not very understandable for foreigners who have no idea of the feud between Amsterdam and Rotterdam. There are various themes such as water, prosperity, power and the canals as world heritage but where is the cohesion? Who is the narrator in this room, whose are the statements on the wall?

Team Pink Room, photo Annemarie de Wildt

For regular visitors, it does not appear to be a space where they linger, despite the comfortable seating. This space in the middle of the exhibition could act as a bridge, in which visitors are challenged to think about their own ideas with which they come to the city. The Russian Liya holds a witty consideration of the color of the hall. Once again I realize the divergence of assumptions people bring to the museum. "Why would this room be pink?" I had proposed them as a research question. Liya says that the word Amsterdam is masculine in Russian. She therefore thought of Amsterdam as a male city. But pink arouses associations with female and gay. And there are also many female personifications of Amsterdam in this room: from the city virgin to a cartoon of a woman in costume with a joint. “So Amsterdam is a woman after all”, Liya concludes.

Discussion in the Pink Room, photo Annemarie de Wildt

In general, the participants in the training course comment on the lack of interactivity, also in the other spaces of World-City. It would be good if the museum caters to various learning styles. It would also be good if there were some more contemporary examples in this room, such as the I Amsterdam letters and campaign. To go around the museum with foreigners is always a good lesson to find out if we are understandable. Hoi polloi (the Greek word for 'the common people' in the English translation of a quote on the wall) is intelligible to many people. Most foreign tourists will also not know that Mokum is, an originally Hebrew, name for Amsterdam.

World-City revisited

The last room of the World-City exhibition was analyzed from a Thai, American, Indian and Sri Lankan perspective by Hatairat Estrella Montien from the Baan Hollanda Center near Bangkok; Kathryn O'Dwyer from Hermann-Grima + Gallier Historic Houses in New Orleans; Juhi Sadiya who is teaching at the National Museum Institute in New Delhi; and Pubudu R. Samanthilaka of the Department of Archeology in Sri Lanka.

Hatairat Estrella Montien discusses the bells without stories, photo Annemarie de Wildt

The team is full of praise for the fact that the room connects past and present. But it does so in a somewhat too simplistic way. The opening text states that until 1950 Amsterdam was a city with inhabitants from Europe. During the two course weeks, they learned, for example during the Black Heritage Amsterdam Tour, that there was indeed a (small) black community in 17th and 18th century Amsterdam. Estrella emerges as a true fan of the Amsterdam Museum, which she frequented during her previous studies at Reinwardt. "What happened to the stories at the Bellenbord (from one of the demolished high rise buildings in the Bijlmer neighbourhood)? It was such a wonderful interactive object where you really met all sorts of Amsterdammers. Such a shame that the interviews are no longer there.” The team also asks about the portraits of Stephan Vanfleteren : who are these people? They now hang here as an illustration of diversity, but what do they think of Amsterdam and its (colonial) past?

World-City Revisted with the work Colonies by Iswantho Hartono, photo Annemarie de Wildt

The team finds both Colonies by Iswantho Hartono and Paulina by Ken Doorson valuable art works that can indeed make you think about how the past affects the present. But for that to happen the museum would need to challenge the visitors more, by asking them questions and giving them the chance to leave their ideas behind. They refer to the emotion networking workshop of Imagine IC, where a good connection was made between stories and objects.

Empathy

The training and analysis of the museum rooms of the Amsterdam Museum provided learning and insight, also for us as museum staff. Both the 'Golden Room' in DNA and World-City would benefit from paying more attention to other perspectives, from other parts of the world, with new ways of storytelling and above all, with more empathy. Many thanks to the participants in the training for this valuable input.

Thank you Kathryn O'Dwyer for editing.

Dutch version see here